The Day Loop

Keshav Agrawal

When the bell rang at 7:50 a.m., it sounded exactly the same as it did every morning — a sharp, hollow clang that made the plaster shiver and the fluorescent lights hum. Sam looked up from the edge of the stairwell, sketchbook balanced on his knee, and watched a thin snow of chalk dust fall from the ceiling into the shaft of light. The dust had a smell: dry, like old homework and yellowed paper. He could have told you, without thinking, where the lost pencil would be under Mrs. Baines’s desk, how the janitor always left his mop propped by the back door at exactly 8:15, and that the cafeteria served lentil soup on Wednesdays.

On the third day of school, Sam discovered he was bored in the way a clock discovers it has too many hands: pointless and entirely aware of its own motion. He doodled a small rocket on the corner of a worksheet and imagined launching himself through the school's skylight. Two pages later the bell rang again and the rocket was still a pencil-shadow on the paper.

It was Rudy who teased the corners of Sam’s restlessness into a map. Rudy was the kind of friend who kept his shoelaces tied in neat knots and who measured things twice because “you never know which half is the right half.” He was small with a quick, nervous laugh and a brain that ran like a precise clock mechanism — always finding the hidden hinge. When Sam pointed out the repetition, Rudy’s forehead creased, and something like curiosity spread across his face.

“You mean like… déjà vu?” Rudy asked, then shook his head. “No, that’s not it. This is too regular.”

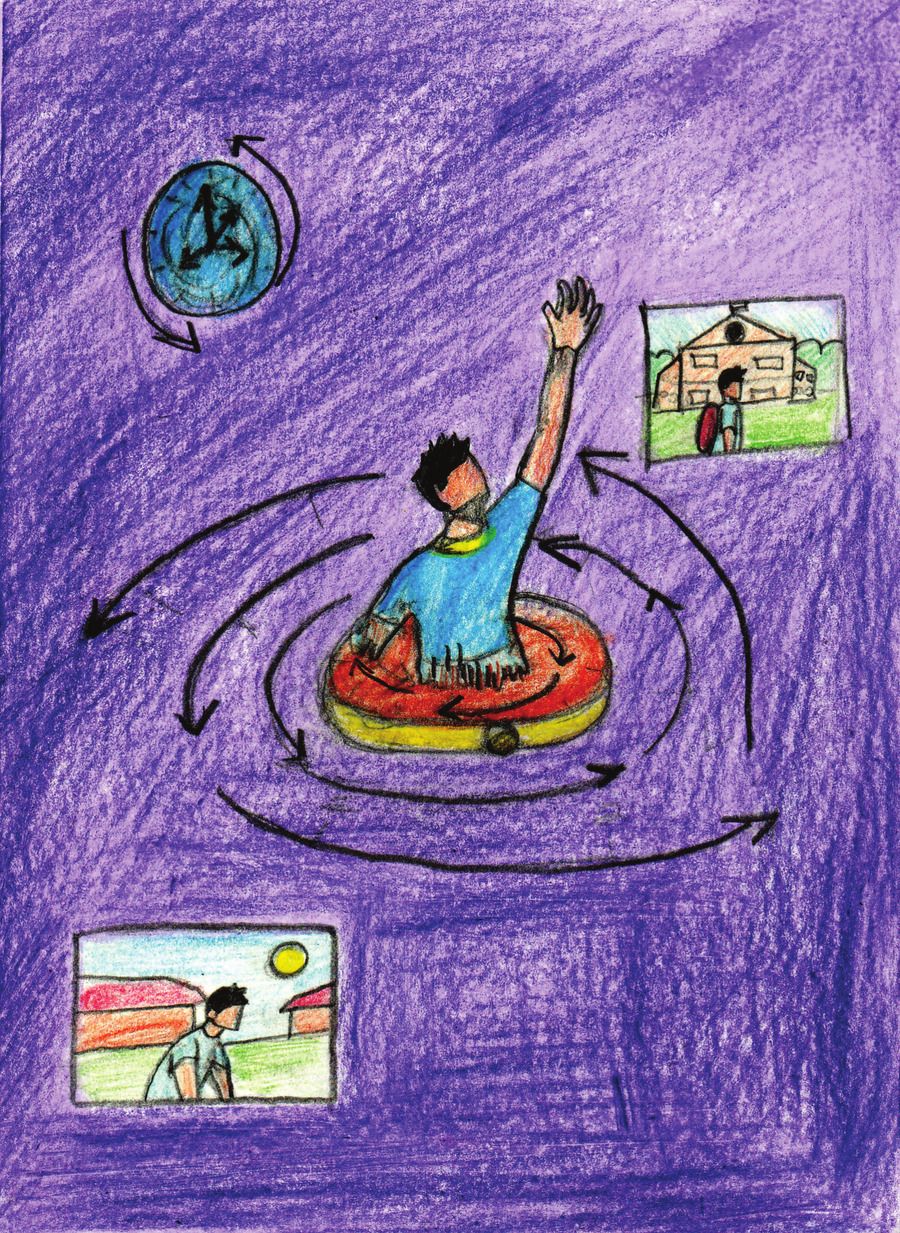

Sam tried to laugh, then stopped because the laugh belonged to a line he’d heard before. He had thought of the loop as a braid of small annoyances: the same joke in homeroom, the same two kids arguing over the same mystery novel, the same blue marker leaking under the same desk. He had not noticed it at first because—adventurous, curious, creative—he always attached new meanings to old things. But after the fourth repeat, there were no new meanings left.

The first time he tried to break it, it was small and reckless. Sam ducked into the dark storage closet behind the gym and stayed. The world outside came and went like a film projector on repeat: Rudy’s footsteps, the bell, Mrs. Baines’s voice calling an attendance roll. Sam waited for the reset, expecting the morning to simply catch up with him and his new place, but instead he felt the room tilt and the same bell reverberated through the thin wood. He stepped out, and there he was again at the top of the stairwell with the sketchbook, the same crumb of chalk between his fingers.

He tried the obvious escape next: he ran. He sprinted across the courtyard, through the chain-link fence, and kept going until the school was a square behind him. The sky was a pale and wrong kind of blue. He sprinted until his lungs burned and then — because the loop had rules he hadn’t yet learned — he found himself sitting at the cafeteria table again, spoon in hand, lentil soup steaming into the same small cloud of steam as if nothing had happened.

“Maybe it’s the school,” Rudy said one night, voice low over a shared flashlight under Sam’s jacket. They were in the abandoned greenhouse behind the art wing — Sam’s favorite place to imagine new suns. “Maybe it’s a… glitch. Like in the old sci-fi shows. Or like when you get stuck on the same level of a video game.”

“If only it were a game,” Sam muttered. “Then I could just find the cheat codes.”

Rudy’s response was a soft huff. “Or we find the map.”

They tried patterns, sequences, and noise. Rudy documented everything in a thin spiral notebook: times, smells, odd coincidences. Sam, whose curiosity was a living thing, proved more desperate with each repeat. He tried sleeping in the classroom, tried staying awake through two whole days and a night, tried ignoring the bell. Each trial taught him a rule: the loop reset at a point that felt like the end of morning, always before lunch, always with that bell’s hollow ring. Death—once, terrifyingly, Sam tested what he had only read about in stories. He stood on the roof and watched the world become a thin, trembling platter. He closed his eyes. He let go.

When he opened them, he was back on the stairwell with the sketchbook on his knee and chalk dust in the light. The rope of existential horror tightened at his throat. Being unable to die in a place that kept repeating everything had the coldness of being a ghost that others could still touch.

After that attempt, Sam’s laughter grew brittle; his curiosity folded in on itself and hardened into paranoia. He stopped trusting the ordinary. He started noticing micro-variations he had missed before: the librarian, Mr. Rutherford, who rearranged the returns in a different pattern each morning; the math teacher's hand tremor; a poster in the hallway that sometimes said “Science Fair” and other times “Art Week.” Small incongruities became islands he used to navigate— until one day, walking past the library, he felt the entire world pivot.

Mr. Rutherford had the kind of face where each wrinkle was a sentence that had been read silently for a long time. He wore tweed even when it was hot, and his glasses always sat at the perfect angle on his nose. Sam had hated the library because its silence felt like being watched by a patient animal; he avoided it like a promise of homework. But that afternoon, something inside Sam sent him there — or perhaps the loop sent him, the way a river chooses its bed.

“Sam,” Mr. Rutherford said without looking up, as if the boy’s presence had been anticipated down to the breath. “You look as if you have been learning the wrong lessons.”

Sam stammered. “I—what do you mean?”

Rutherford closed a book — not on top of the pile but within its own invisible order. He had a small, curious smile. “You are not the first person to notice this pattern,” he said.

Sam’s chest tightened. “You know about the loop.”

Rutherford’s eyes were thoughtful. “There are things that happen to people who spend their lives cataloguing possibilities. Books contain many maps. Some maps are literal. Some are not. I spent years trying to treat the world as if it had a spine I could trace; sometimes the tracing bruises you.” He tapped the card catalog. “The school is full of books. The books are full of choices. But there are also… rooms between the shelves that knowledge keeps to itself.”

It wasn’t really an explanation. It was an invitation.

“You’ve been stuck?” Sam asked, voice thin.

Rutherford’s thumb brushed the spine of a book. “Once. When I was young and stubborn. I thought I could outwit it alone. I learned instead that some loops are mechanical, and some are mnemonic. Some you can attempt to brute-force, but the only way out is to learn the code that made it.”

They began with small things. Rutherford taught Sam to listen to the library as if it were a body. The flick of a page could be a heartbeat. The shifting of books could be a sigh. They wore gloves and walked between stacks, reading titles aloud like charms. Rudy, who had been waiting outside the library’s heavy oak door like a guardian, joined them. His notebook filled with possible patterns and logical trees; his hands trembled, but his mind was clear.

The library, which had always been orderly and inert, seemed suddenly to move like a living room rearranging itself to accommodate a darker conversation. Shelves creaked. A ladder here, a hidden hinge there. Rutherford guided them to an old, unmarked folio that smelled of glue and lemon oil. It contained sketches — not of birds or stars, but of circuits, loops, and sequences stitched together with phrases in a language of math and metaphor.

“Simulation theory, psychometrics, narrative traps,” Rutherford murmured, scanning the pages. “The family-run educational labs did a lot of experiments in the earlier century. Not all of them were ethical.”

Sam’s stomach dropped. “So we’re—what— part of someone’s experiment?”

Rutherford folded the paper carefully. “Possibly. More likely you are inside a constructed trial. The important thing is this: loops are not always meant to torment. Sometimes they are diagnostic. They compress a life into a slice to test a few things. The trick to escaping is to satisfy the test in a way that the testers did not predict.”

That idea felt like a window opening and immediately slamming shut. If the loop was a test, then perhaps every repetition was a question. Sam began to think in questions. Where are the anomalies? What keeps changing? What response breaks expectation?

They experimented, but this time smarter. Rudy applied logic; Rutherford supplied hidden knowledge about patterns and languages; Sam applied his adventurous streak to invent unexpected answers. They made choices that were deliberately illogical: Sam whispered a lie during roll call; he refused to submit homework he had already completed; he skipped the safety drill and staged a recitation in the hallway. Each time, the loop tightened and reset with the same bell, but something shifted ever so slightly — a pause, a delayed step, a blank space between sentences.

Finally, Rudy found the smallest hinge: a string of seven words Sam had repeated unconsciously whenever he felt alone — fragments of a poem he had written when he was seven and afraid of thunderstorms. The phrase acted like a code. When Sam refused to say it, the bell tolled, and the stairs blurred. When Sam rewrote the poem aloud but with different punctuation and made a choice that felt impossible — he forgave someone in his heart who didn’t ask for forgiveness — the world shimmered.

Rutherford shut his eyes and listened as if attuning to a harp. He opened them and took Sam’s hand. “Now,” he said, “say your new line. Not the old one. The one you choose.”

Sam inhaled, and this time the words were not a rehearsal but a declaration. He created a sentence and placed it like a key into the lock of the day. The bell rang, the lights dimmed, and for a breath the entire building exhaled.

When Sam blinked, he was not on the stairwell but in a room that looked like a hospital waiting area folded into a living room. Screens lined the walls, each filled with someone’s face: his mother, his father, his little sister, and a team of technicians wearing soft smiles and harder badges. Everything smelled faintly of sterilized air and coffee. His heart hammered against ribs that felt newly fragile.

“What—” Sam started.

“Welcome back, Sam,” his father said, standing. His voice was gentle but hollow, like a recording lowered to spare everyone’s nerves. “It’s okay. You did very well.”

Rudy — who was sitting beside a bank of monitors, wearing the same nervous half-smile — looked as if he had stepped out of a storyboard into reality. Mr. Rutherford, in a jacket that had somehow been a costume, nodded with the calm of a man who had expected a scene to close like a curtain.

Sam’s first immediate reaction was betrayal — a hot, animal swathe of it. “You set this up? You trapped me inside a repeating day? For what?”

His mother stepped forward. “To measure cognitive resilience. To test creativity, problem-solving. We—everyone here—wanted to know how you’d handle a compressed diagnostic. We didn’t mean to scare you.”

Sam felt the air rush out of him; the world that had been so mechanically precise while it looped suddenly seemed flimsy. “So my fear wasn’t real? My attempts—” He stopped because his attempt to jump from the roof, the terror, the helplessness — the memory of it — felt very, very real.

Rutherford watched him with sad, steady eyes. “The loop was real. The fear was real. But the parameters were designed. That does not make your feelings any less true.”

Sam thought of Rudy’s spiral notebook, of the way his friend had traced logic like footsteps. He thought of the greenhouse and the smell of soil, of the lentil soup that had tasted like a memory. He felt anger again, but it was braided now with something else — relief, maybe, and an unexpected gratitude toward Rudy and even toward Rutherford.

Rudy, voice small, said, “You weren’t alone in there, Sam. I… I knew after a few runs. They let me watch. I tried to change things from the outside. I studied your pattern. I wanted to help.”

Sam’s legs gave way and he sat. The technicians—kind, competent—seemed unsure how to proceed now that the test had ended. Sam’s family moved around him, gentle and apologetic, their faces full of the earnestness of people who had convinced themselves that knowledge was worth a bruise.

Later, when the room had emptied and Sam sat alone with Rutherford on a bench watching the city lights, he asked the question that had been at the core of him since the stairwell: “Why me? Why do this to your own son?”

Rutherford folded his hands. “Because sometimes, people who love you mistake a test for a ladder. They build a way to measure the place you would naturally grow. They think their method will pull you up. It’s an error of imagination.” He tapped the bench between them. “But you found a different method. You made choices that weren’t part of the script. That shows something important. It shows you.”

Sam stared at the lights. The loop had taught him his limits were not walls; they were questions he could answer in unexpected ways. He had been trapped, terrified, and creative all at once. He had lost the illusion of ordinary safety and, in the cost of those lost days, found an odd kind of courage.

Rudy nudged his shoulder. “So… no more lentil soup on Wednesdays?” he asked, offering a ragged smile.

Sam laughed, and the sound was a little cracked but bright. “We’ll get a new menu. And maybe a new way to measure curiosity—less terrifying, more… basketball drills?”

Rudy brightened. “Yes! And we’ll also—” he hesitated, then added, “—keep the greenhouse.”

Outside, the city hummed. Inside, Sam folded his sketchbook and made a new drawing: a ladder that led to a rooftop where the sky was big and not a loop. He shaded the top of it with the same small, stubborn optimism that had dragged him through the repeating days.

He would always remember the smell of chalk and lentil soup and the exact pitch of the bell that had haunted him. He would remember the trap and the men who made it. But as he looked at his friends, the people he loved stumbling forward into the same uncertain world as him, he realized that the true test had been less about measurement and more about choice.

When he finally left the lab, Sam walked into night as though stepping into a new chapter. He had been bored once — bored in the old way, of sameness — but he was not bored anymore. He had learned that even when days loop, a single new sentence, a different choice, could break a pattern. And somewhere, toward the top of his sketch, the little rocket he had drawn months before had a tiny door cut clean through its side: an exit he had wit and friends enough to find.